by Dr. Eli Steenput

This article offers background information on my presentation at the 2007 HEMAC conference in Dijon. It describes a number of principles and observations (on this page), illustrated with applications. It also presents a grouping of the dagger techniques from Hans Talhoffer's works.

My main argument for grouping techniques together is that they start out from a similar response, and thus can be seen as situational variations on a common principle. I think this allows us to make useful observations about the possible reasons to prefer one technique over another in a given circumstance.

I distinguish the following major groups (linked to the source material and my interpretations, on separate pages):

- Guards and attacks: source - interpretation

- Defenses against a low stab: source - interpretation

- Punt wider Punt: source - interpretation

- Schilt: source - interpretation

- Versetzen with the left arm (inside): source - interpretation

- Versetzen with the right arm (outside): source - interpretation

This replaces my older interpretation (presented in 2005) based only on Cod. icon. 394, 1467.

Sources

I made a study of Hans Talhoffer's dagger techniques, based on his following works:

- MS Chart. A 558, Gotha, 151 folia, 178 drawings, 41 pages of text, 1443. [gotha]

- P 5342 B (Cod. Nr. 55 Ambras), 73 folia, ca. 1450. [ambras]

- Thott 290 2, Kongelige Bibliothek, Copenhagen, Hans Talhoffers Alte Armatur und Ringkunst, 150 folia, 1459 [alte]

- Cod. icon. 394, 137 folia, 1467. [fecht]

In [gotha], the dagger section comprises drawings 82-125. Unfortunately there are no captions. Unlike the later manuals, most techniques have at least two drawings devoted to them. Due to numerous inconsistencies (such as different dagger grips between the pictures) and poor artwork, this is not as helpful as it might at first appear, and many of the techniques remain hard to interpret.

In [ambras], dagger techniques go from page 43 to 63. This manual is interesting because it tends to show techniques from different angles than the other manuals. It is slightly unusual in the high proportion of unarmed defenses shown (9 out of 20).

In [thott] the dagger section goes from folio 61 to 71 (19 plates). This work shows all the fighters inside a duelling arena.

In [fecht], tafel 170 to 190 deal with dagger (two drawings for each tafel). All techniques are dagger vs dagger. Many of the drawings are very similar to [thott].

My interpretation

We do not know for certain how the techniques were performed. Every interpretation is of necessity based on certain assumptions - such as that the techniques were effective and made sense.

My own assumptions can be summarized as follows:

- the dagger fight is based on the principles of the German longsword in the Liechtenauer tradition (as set down by Dobringer and Ringeck).

- the dagger system is not a large set of disparate "tricks", rather there are only a fairly limited set of responses, with lots of situational variations.

Much of my inspiration comes from Matt Galas' system for explaining longsword as application of a limited set of positions and transitions, and Colin Richard's situational use of techniques.

The principles

- simple, direct, fast, short

- take initiative, keep moving

- strike to the openings, don't defend without offense – it is dagger vs dagger, not unarmed against dagger, so use the dagger you have

- fuhlen: use soft technique when he is strong, use strong technique when he is weak

- better one good strike than six bad ones - committed attacks, keep point on target.

- better strike high than low - 80% of techniques are against high stab

- better work on the sides than straight

Selected quotes from Hanko Döbringer

(David Lindholm's translation)For you should strike or thrust in the shortest and nearest way possible.

real fencing goes straight and is simple in all things without holding back

you must strike straight and direct to the man, to the head or to the body whatever is the closest and quickest. This must be done with speed and rather with one strike than with four or six which will again leave you hanging and giving the opponent a chance to hit you.

Do not strike at the sword, but always to the openings, to the head, the body if you whish to remain unharmed. If you hit or miss, always search for the openings, in all teachings turn the point to the openings. He who strikes widely around, he will often become seriously shamed. Always strike and thrust at the closest openings.

You should always look for the upper openings rather than the lower. The upper touch is much better than the lower. But it may also happen that you are closer to the lower opening and therefore seek it, as often happens.

And always be in motion, this will force the opponent to be on the defence and not be able to come to blows himself. For he who defends against strikes is always in greater danger than the one who strikes, since he must either defend or allow himself to be hit if he is to have a chance to strike a blow himself.

If he moves off when you have come on the sword in front of one another ... follow him with the point and do a good thrust to the chest or something like that as quickly and directly as you can. That is you should not let him escape unharmed from the sword.

No complete system

Talhoffer's dagger material does not represent his complete system. Each manual has unique techniques that don't appear anywhere else. Also, not everything is explained, for example, the technique ober Schilt is shown in each manual, but only [ambras] mentions that the point of the technique is to take the opponent's dagger away, and only [fecht] shows one (and only one) way to do this. He then goes on to show six counters to the technique. Fortunately, we known several ways of taking away the dagger from the ober Schilt because they are explained in other manuals (like Codex Wallerstein). But based on only Talhoffer, one could easily draw the conclusion that ober Schilt is no more than a passive block. So it is important to ask whether a drawing shows the start, middle, or final position of a technique.

Talhoffers way of disarming the enemy from upper shield

An alternative from Fiore

An alternative from Wallerstein

Dagger versus dagger

Talhoffer's techniques are generally dagger versus dagger, very few techniques are shown ONLY unarmed versus dagger. This is relevant for the way the techniques are performed.

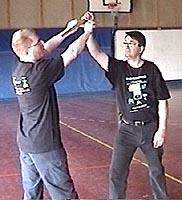

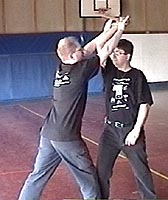

For example, the scissors technique, as done nicely during training:

A student of "modern" knife fighting may be tempted to slash the wrists before the lock is applied. This usually results in both students trying to do their tricks faster and faster, and finally conclude that the technique doesn't work:

Slash!

So, what is the factor that makes the technique work that was forgotten? Simply this: the defender also has a dagger!

Look where this thing is pointing...

If the defender makes his goal to put his dagger into the enemy, the enemy will be forced to push back - an attempt to withdraw and slice will end with a dagger in his chest. This leaves the defender plenty of time to apply the scissors technique.

In terms of longsword principles, we see a zufechten, an anbinden when the combatants' arms touch, and an attempt at abnahmen countered by nachreisen!

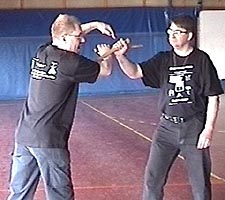

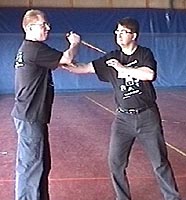

The versetz with scissors shows this idea even better - the point is not just

to deflect the attack, but to stab the enemy while doing it.

Even unarmed, the versetz with the scissors is not a passive defense, it ends

with the enemy's own dagger in his skull.

All techniques are situational

Every technique is situational, most are situational variations of the same principle. If the technique is not matched to the situation, it may not work.Some important variables are:

- your posture, dagger grip

- direction of attack

- distance, enemy posture

- weak or strong

- early or late

- reaction of the enemy

There are only a fairly limited set of responses, with lots of situational variations.

Posture, dagger grip

For example, this simple inside deflection:

Depending on how the dagger is held, the defender counters by a stab high or low, or a disarm when he is unarmed himself:

Direction of attack

If the angle of the attack is different, the exact same technique can be applied at the other side:

Distance, enemy posture

Another type of situational difference is distance. In training we usually adjust distance to match the technique, but in combat it makes more sense to vary the technique depending on the distance. For example, if we end up a little too close for the previous inside deflection, we go for the arm instead of the wrist. We can lift the leg if it is within reach.

It would be very awkward to try the wrist technique from this distance:

Timing

Timing is another situational variation. This set of armlocks (unarmed or with dagger) works very well when we intercept the attack early (or the enemy tries to pull back from contact):

On the other hand, it is very difficult when we are late and the enemy is pressing forward:

Two techniques show an outside deflection with the left hand, which might develop from a mistimed or feinted inside deflection:

from the position in the last picture, you throw up your legs and drop on the

enemy's head with your full weight (not shown)

Weak or strong

Another situational variation depends on feeling (fuhlen): if the enemy is pushing strongly forward, the grosser worf is a natural choice - very much like durchlauffen with the longsword:

you're supposed to throw your full weight on his arm, then stab him while he's

down

If the enemy is soft, this strongly entering elbow push is a much better choice:

Reaction of the enemy

A final type of situational variation is the enemy reaction. The enemy will usually not just stand there waiting to be killed. For example, if the enemy pulls back during the set-up of grosser worf, this elbow lock follows naturally:

There's a counter to it, of course:

Another example: this very elegant and deadly response to an attack leaves the enemy with few options:

He could try to evade, which sets him up very well for this leg lift:

If he evades to the other side, he easily falls into this throw:

In conclusion:

Talhoffer's dagger techniques can be interpreted as an effective and coherent system based on clear principles. To understand the true value of the system, it is necessary to consider the situational context that makes techniques obvious, natural, and powerful. I hope this article may prompt my readers to discover more such applications for themselves.